Holocaust Recollections, Lior Israel: Difference between revisions

Israel-Lior (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Israel-Lior (talk | contribs) |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

Before final planning of the project, I first aim to built a wide-scale try-and-error sandpit of conceptual and spatial ideas which would in turn eventually develop into the concretisation of the monument. | Before final planning of the project, I first aim to built a wide-scale try-and-error sandpit of conceptual and spatial ideas which would in turn eventually develop into the concretisation of the monument. | ||

== '''Program''' == | == Part I: '''Program''' == | ||

== ''' | == Part II: '''Anthropology Essay''' == | ||

== '''Conversations''' == | == Part III: '''Interviews & Conversations''' == | ||

== '''Memorial Study''' == | Establishing a critical idea and defining an approach, is the first building-stone in developing my architectural work, as I strongly believe in the dialectic nature of social aspects that form architecture, which in turn, transforms society. Architecture is a language, a form of expression that makes concrete an abstract idea. It is a pure representation of a given time and place, of an epoch and mindset. Hence, my work ahead must begin with identifying unambiguously my area of intervention; Israel, 2018. How would the architectural representation of the Holocaust develop throughout the lives of 3rd generation survivors; when the last individual who bears their immediate personal memories of the Holocaust pass away? To answer this question, I will first assess and define my contextual situation. | ||

== '''Site Analysis''' == | |||

== '''Concepts''' == | Recallection of Loss? | ||

== '''Planning''' == | Once a year, every year, 86% of the Jewish population of Israel stands still in silence for 120 seconds. In their minds they imagine and replay the most horrific event that happened to the Jewish People in modern history - The Holocaust. This memorial “minute of silence”, which actually lasts for two minutes, takes place on the Israeli Memorial Day for the Holocaust and Heroism, held annually on the 27th day of the month of Nisan, marked on the Hebrew calendar. But what exactly do all these people remember? | ||

As time goes by, the Holocaust changes its nature from a concrete historical event, such that can be talked about, discussed in an academic manner and referred to by documents and historical facts, to a timeless event of mythical proportions, deprived of any real contextual basis. As part of this process, one might suggest that in Israel, the state makes use of the Holocaust to achieve goals that may indeed be to the benefit of the country and its people, but consequently turn the historical event into a tool - The Holocaust for itself loses its position as the main focal point and no one truly bothers with its effect on the way it is widely remembered and understood colloquially. | |||

It would have been logical to assume that as years go by and the State of Israel becomes a stronger and a better established country, the magnitude of anxiety, the so called “fear factor” of the Jewish Israeli People, should diminish. Yet, on a poll conducted by an Israeli newspaper in 2013 (2), 49% of all Jewish Israelis said that they believe a second Holocaust for the Jewish People is highly likely to happen in the future. On a similar poll held in the 1970s among Holocaust Survivors, which asked if they believed a second Holocaust is likely to happen to the Jewish People, only 46% of the inquired answered “Aye”. | |||

In Israel of today, it appears that the narrative of the Holocaust is unfortunately, oftentimes detached from its contextual history. | |||

It is widely accepted that in the past, during the first decades for the young country of Jewish immigrants, this horrific event was used by the leadership to establish a solid collective identity for Jews of different geographic and ethnic backgrounds, whereas today, it is institutionally turned into the “ultimate event of horror” which Israeli Jews experience as individuals, rather than as a group. One could therefore even wonder: What is the public role of the Holocaust in Israel, when the state finds it difficult to even offer the proper care and institutional old-day respect for Holocaust survivors, in the last years on their lives? | |||

The KZ Syndrome, or, Survivor Guilt | |||

The Konzentraztionslager Syndrome is a prevalent and prevailing mental condition which occurs when an individual believes he or she have done something wrong by their very survival of the horrors of the Holocaust. It is accepted today as a significant extreme symptom of a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. | |||

A Post-traumatic event is “stored” in the human brain differently than a normal memory of a past experience; such memories of profound fear and angst never make the typical process from a short-term memory to the deeper, more vague long-term memory. They remain fresh and vigilant, as if the event of horror only recently happened. The panic, the anxiety, the sights, the smells, the feelings - all the emotions that were experienced during the painful event are re-lived. For the victim, they come back to life in the here and now. For the Holocaust survivor, the war has never ended; it is still going on, it is still a daily struggle. | |||

The Holocaust, 1939 - ... | |||

A non-immediate portion of the war and its horrors is still with us today through the fears and lives of second and third generation survivors. | |||

In a 2015 study conducted by Dr. Rachel Yehuda (3), she revealed that Post Traumatic events cross generations and transfer on to one’s offsprings through a change in the genetic sequance and subconscious psycological recations. | |||

Decades before the existence of the State of Israel, the natural thought of the early leaders of the Zionist Movement was to rely on Central and Eastern European Jewry for the future population of the country. | |||

After the tragic and terrible human losses of the Holocaust, as the State of Israel was established, hundred of thousands of Jews emigrated to it from the Arab world. The social composition of the country started changing - Israel turned into a Jewish multicultural society. | |||

The local leadership had to find a consolidating narrative to help turn all the different people, with all different backgrounds and different languages, into a monolith nation with a single identity. The Holocaust was turned into a pathos melting pot of a unifying victim ethos. | |||

One of the strongest examples to this type of usage of the Holocaust as a tool was frequently done by no other than the late Prime Minister of Israel, Menachem Begin, whose parents perished at the hands of the Nazis. However, the truth remains as all streams of the political spectrum in Israel, whether belonging to the Right or to the Left, either done by Ashkenazim or by Sepharadim, everyone made and makes use of the Holocaust as a tool. | |||

Forgive and Forget? | |||

On a 2015 survey conducted for the 50th anniversary of the official diplomatic relations between Israel and Germany (4), 69% of the represented Israelis held a positive | |||

perspective towards modern-day Germany, which may bring up the question: How is it possible that in Israel, out of all places, the Holocaust has been detached from its historical roots in Germany? | |||

Yet, as matter of fact, to formulate memories of a distant historical event, it does not matter where on earth the event originally took place. For all its worth, there seem to be no external circumstances, only subjects with personal memories; or as the controversial quote said by the former Prime Minister of Great Britain, Margaret Thatcher: “There is no such thing as society; there are only individual men and women, and there are families”. | |||

The memory of the Holocaust in Israel today is arranged exactly by this condition, which sadly allows manipulation for almost any contemporary need. In order to manipulate a traumatic historical event, it must first be turned into a set of fears. The question which arises: Has anyone turned the Holocaust into a set of fears deliberately? | |||

In my opinion, not necessarily. This result was the outcome of a larger, slow process of transformation from an adhesive common identity to a deconstructing individual identity. In other words, a form of “social privatization” which led eventually to turning a historical event into a practical, political tool. | |||

In Naomi Klein’s book “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism”, the researcher describes the way the masses can be controlled through a constant stage of fear, horror and a sense of helplessness. Who could possibly deal with mundane topics when one’s very existence is on the line?! | |||

In a similar manner, the Holocaust within the Israeli discourse became just that. It was detached from its historical context and was turned into the ultimate, infinite evil. A tool through which an entire nation stays in a constant Post-traumatic Disorder for over 70 years. | |||

The biggest question I want to ask with my work is whether it is possible to recollect and represent the Holocaust in the Israeli public sphere, in other alternative ways as well; ways that impose less indoctrination and offer fewer summoned answers. The alternative commemoration I seek should allow an open-end for thoughts and feelings. | |||

In 1988 the late Israeli historian Dr. Yehuda Elkana, a Holocaust survivor himself, published a controversial article in the Israeli newspaper Ha’Aretz, by the title “The Need to Forget” (5), in which he emphasizes his personal point of view that there is no greater risk for the future of the State of Israel than the ever-present traumatic memory of the Holocaust in the national consciousness. | |||

Dr. Elkana argues that the anxiety of the Holocaust is breastfed to every boy and girl in Israel from the age of infancy, that the educational system in Israel sends the youth year after year to repeated visits in Yad VaShem, visits which create memories that the youth cannot benefit or escape from. He argues that the nation must let go of the bleak past, try to put the trauma behind and strive to heal, for its own benefit and for its own future survival. | |||

We Won’t Forget; We Won’t Forgive! | |||

In August 2016, my wife and I went on a three-week long summer vacation to Poland. It was my first ever visit to the country. We rented a car and drove across it from East to West. We had all the time we needed to explore anywhere we wanted. | |||

During this trip, my wife kept asking, just as she had done before we even arrived to Poland, why should we not see any of the Death Camps, or at least Auschwitz-Birkenau, as we were staying in Krakow for several days and the site is nearby. It was certainly interesting to see, she argued. | |||

My answer to her was that I don’t need to visit Auschwitz-Birkenau as I have already been there. In fact, I visit the place several times every week and perhaps, I never left. | |||

A visit to a Death Camp is an experience I personally do not feel the need for. The educational purpose of it is unnecessary for my knowledge, as I know pretty much already know everything there is to know about the Holocaust and the Death Camps. For me, it is not vital to see piles of victim’s shoes or forsaken crematoriums with my own two eyes. I know what happened, I feel very deeply about it and its physical existence cannot contain any new message for me to grasp on, except for grief and hurt; grief and hurt that are already a part of who I am. | |||

Moreover, the unimaginable evilness that gave rise to the Holocaust is not to be found in the barbed-wires and train tracks of Auschwitz. It is also not to be found in any gas-chamber or a crematorium. This monstrous viciousness lied only within the wicked hearts of those who stood behind it. Once I understood that, I figured out I do not need to visit any death-camp. | |||

Yet, during this trip we did visit a small town by the name of Sokołów Podlaski, about an hour-and-a-half drive Northeast of Warsaw, where my late grandfather used to live. I tried to find the now non-existing synagogue, the old Jewish school my grandfather used to attend, and see what life must have been like for him, living there. | |||

It is very likely that for many non-Jews, perhaps for some Jews too, a visit to a Death Camp is an important educational study-trip, much more than a visit to a random, forgotten Polish town. The sites of the camps are of an utmost historical importance - there is no doubt about that. Although personally, it is an unnecessary trip. For me, seeking a “living past” is more intriguing and relevant than finding the place where this past was put to an abrupt and unjust end. | |||

In our visit to Poland, I tried to experience the country as little as possible through the lens of the Holocaust. It may be quite impossible for a third-generation Jewish survivor, it may be impossible for an Israeli who grew up in the country and was raised there - but nonetheless, I tried. | |||

During our three-week stay in Poland we did not visit a single Death Camp. | |||

=== Dr. Dr. Roni Stauber === | |||

'''Lior Israel:''' How would you define the memory of the Holocaust and its presence within the Israeli civic sphere since the founding of the country? | |||

'''Roni Stauber:''' The process that happened to the Holocaust in Israel over the years is that it has become a ‘civil religion’. I suppose you have already encountered this claim, as I am not the first to have said that. I say ‘civil religion’ since it certainly has the right characteristics and hallmarks of sanctity. | |||

How is it manifested? Well, indeed when the term ‘Holocaust’ is at use, sometimes, or even frequently in many different analogies, it may often create a negative reaction among the public which asks: “Why would anyone use the Holocaust’s name for such purposes?!”. | |||

Some do view its mundane use as a desecration of something holy, or a form of blasphemy. There is always a debate around it. It is not a neutral concept as many other concepts are. | |||

The Holocaust, in this sense, is a bit like the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem - something holy. | |||

But the Holocaust has not always been this way. It has gone through changes in the Israeli society. The Holocaust was not seen the way it is seen nowadays in the 1950s, for example. As we become further distant from the actual happenings and events, the Holocaust is not perceived as just ‘another’ historical event, as one would have imagined, but quite the contrary - it grows into mythic sizes. It is a paradoxical manner that is true in correlation to the Holocaust not only in Israel. | |||

The normal process that happens with other historical events does not seem to happen in the case of the Holocaust. | |||

The fact is that a lot of effort in research and study is carried out about the Holocaust. I would ask to separate the public discourse in the topic from the research activity attitudes, since it is the research activity that truly puts one ‘into’ the Holocaust; Which brings it down from its mythic pedestal back to earth, and allows us to have greater insights. | |||

Yet, as Friedländer and others researchers have said, one is still unable to fully comprehend the meaning of what Auschwitz actually was. The gap is ever-present, we know that, but from many standpoints the research does shed light on the more ‘practical’ sides of the Holocaust - it helps to understand what brought the perpetrators to such moral abyss, it assists to the understanding and mapping of Nazi bureaucracy, attempts to explain the personal aspects that eventually sum up into this monstrous creation. And indeed, this monstrous creation has many personal sides to it - career aspirations, obedience, bureaucracy and scary personal sides - some things we may even recognize in our day to day lives - of course that not even close to these horrifying scales, but it is still there. | |||

So again, the research regards the Holocaust as a historic event and analyzes it as such. Even if it is viewed as a precedential and an infrequent, rare event of a state’s defined decision to carry out a complete and total genocide of anther People. | |||

The question that is asked is how much of this concept gets through into the Israeli society and its discourse about the Holocaust - but this is a question I unfortunately cannot answer. | |||

That is to say that in Israel the Holocaust is acted as a myth, a sacred story - for better or for worse. We can discuss it. It is a key element in the Israeli civilian identity and identity of the State. | |||

This is the point where I always say that if you look at the terms ‘Holocaust’ and ‘Revival’: These two terms are key definitions - a combination of words that is basic for the understanding of the Holocaust in Israel. I find it very interesting to see the changes, and this is my own claim, that this combination of words has gone through. | |||

As for my own perception, and you can back it up with my writings if you will, is that in the 1950s the emphasis in Israel was completely on the part of revival and resurrection and the Holocaust | |||

was only perceived as a sort of the “bringing forward” for it - as if the Holocaust were the historic explanation for the later events of Jewish revival and resurrection. | |||

I claim, and I know that not everybody agrees with me, that the dealing with the Holocaust during that time was seen only through the so-called ‘lessons’ we could have take from it, or what conclusion we could have taken from it. But at the same time there was nearly no dealing with the stories of the Holocaust, the atrocities, and catastrophes. | |||

This tendency changed over the years, however. As it changed, and since the survivor’s stories from the Holocaust are so horrific and hard to comprehend, just think of Auschwitz-Birkenau as an example, the Holocaust ended up being molded into ever growing mythic proportions. | |||

L.I.: In what manner do you think the Holocaust should have been remembered in Israel and what should be the way to approach it in the Israeli society? | |||

R.S.: First I must say that I am not fond of the mythic outlook of the Holocaust. In my opinion, it must be taken as a historic event, while keeping in mind all of its true uniqueness and scope, which obligates us to analyze and understand it in non-biased tools. | |||

It should be taken as a lesson for the entire human race, which may also have some national sides, but again, it should mostly be a very important universal message. We should understand the consequences of human behaviour and try to examine the dynamics of mass killings and genocides, how such atrocities begin and carry on happening after people see what they have done, and inspecting the mechanism of bureaucracy - how dangerous and scary it may become when it is pushed into negative extremes. This is what we should understand from it - the alarm from radical, extreme ideologies, from the downfall of society to abyss and collective insanity. | |||

The problem is that because the Holocaust is seen as a sacred thing, because it was turned into a myth and as such, it serves educational purposes - people may extract very contradicting conclusions from it. I would even say that this is one of the defining attributes of the approach towards the Holocaust in the Israeli society today - i.e. people use the story for their own needs. It is the same process that may be done with the Torah. Some may extract territorial and national justifications from it, sometimes even nationalistic justifications - while others may find universal truths such as saying that the Torah calls for equality and peace among nations and mankind, and some others may say that it mostly expresses the right of the Jewish people for this land. It is all possible. | |||

The same principle applies for the Holocaust - if you take the conclusions of the right-wing from it, then their claim sounds something like: “Look at what they have done to us!”, or “Everyone is against us, therefore we must only rely on ourselves!”, and so on - while the left-wing side would try to take it to a universal idea and the fear of what can happen to a society, or maybe to the Israeli society in our case, when people fall into a moral black hole. | |||

I, as a historian... look, broadly speaking, historians analyze every event as a distinct happening - the concept is that every event is unique. This is the basic perception of any historical research. It interests us to examine an incident, a happening. | |||

A historian, as opposed to a Political Science researcher, does not try to find any formulas or repetitional rules. I could even say that we are afraid of general rulings and all-inclusive conclusions, patterns. I am taken aback by analogies. I am very un-fond of it and I do not deal with such things. | |||

Of course that each and every one of us has his/her own thoughts and opinions, but I am very troubled as a historian when personal opinions become the basis for historical analogies. I would have been a lot happier if people dropped aside the analogies of the Holocaust - from both sides, left and right. We should only focus on it as a unique historical event - not a myth that should lead us to an understanding, whatever it may be. We should only understand the Holocaust as a specific, one-time event. | |||

L.I.: Would you say the Israeli society suffers from a post-trumatic disorder due to the memories of the Holocaust? | |||

R.S.: If the claim states that our entire behaviour as a society is irretional due to the Holocaust - No, I would not accept it. Though, of course the question must also refer to the relevant time this post-traumatic disorder relates to. | |||

I think that within the Israeli society there were two opposing forces, existing side by side already from the very beginning of the state. One force pushed towards Holocaust oriented conscienceness, while the other force pushed into other directions, so that the Holocaust would not become a decisive factor in the state’s relation to the rest of the world. You could notice these two forces already from the very estabhlishment of the State, and these forces naturally collide. | |||

My own opinion is that the decisive matters that determine which part of the Holocaust memory is more dominant, for example - the fear from our destruction by our enemies or the chance for peace - these are the factors of our surrounding circumstances. | |||

It is not that we correspond with every event in a post-traumatic behaviour that is detached from reality. I believe that the plain reality does affect our opinions and actions directly. When our true reality is full of concerns about the future, there is existential fear - I do not rule out that the experiences we have had as a People, our collective memory, do henhance this sense of fear. Even if our shared memory exaggerates our emotions - our emotions are still not un-related to reality. | |||

It is not as if our lives here in Israel are the same as the lives of the people in peaceful Scandinavia, and we just make up imaginary threats and fears that do not really exist around us. We do indeed live in an intimidating part of the world. | |||

But it would be improbable to claim that the Holocaust has absolutely no connection to our perception. How could it not? It is part of our memory and conscieneness. Yet, going all the way in claiming that the Israeli society acts the way it does in disconnection with reality and only according to the traumas of the Holocaust; that the Israeli society is completely neurotic and so its acts out of fear and blindness, rather than directly reacts to the situation around it, that is to say, that our alleged actions are only reactions to our memories - no, this is a stand I cannot accept. | |||

I think that our reactions are results of the real world. They could perhaps be over-manifested, and it may as well be that the Israeli fear from Iran, for example, is over-reacted - but such claims I cannot be sure of. I do not possess all the intelegence and information of how dangerous or hateful the Iranians are - but anyway, the Israeli fear is certainly not detached from reality. | |||

To summarize my words - it is obvious that there is influence to the Holocaust, but on the other hand, our actions are not post-traumatic in the sense that we allegedly act in disassosiation with reality. I believe we act rather rationally, sometimes even very rationally, in fierce contrast to what one would expect - Take for example the case with Israel during the Gulf War. One would expect Israel to act in a non-rational manner and retaliate, strike back in Iraq for their missile attacks on Israel. However, the Israeli leadership did no do that. | |||

There are other examples where the State of Israel does not act according to what one could expect from a post-traumatic society. This means that there is rational thinking which is rooted in hard facts and reality. | |||

It may or may not be stratigically correct - this is a matter for other debates - but I do not see the Israeli behaviour as such that is not connected to reality and that we should have all been put into a mental institute, as a nation. | |||

L.I.: Does it mean that in your eyes, the presence of the Holocaust in the Israeli day to day life is more or less normal, taking into accounts the very abnormal event? | |||

R.S.: Yes, in my opinion is it a normal reaction. Memory contradicts with reality in re’al politics. I do not see it as a dichotemy that one side is up and the other is down, as a zero-sum game - that is, that the reason’s side is kept down. I believe that there is contradiction in this as there is in many human behaviours. This means that one might have fears and memories of traumas one has gone though, this may be relevant to each and every one of us, and then we come across the reality and the question that arises is which part overpowers the other. | |||

In my opinion there is a collision between the two things; the Holocaust is present and affecting. I do not think it took over our minds, our ways of thinking and the behaviour of the Israeli society. I do not see it this way. | |||

Although there are undoubtly leaders who exaggerate - I am not completely sure how much of what they say is real and how much of it is just a form of manipulation - but when Netanyahu says this and that, I am not sure whether he truly believes in what he says or simply manipulates the situation. I am sure he fully understands the historical differences between different events. There is a lot of disinformation among politicians in general, and this is another reason why I do not like what they make of it. I am taken aback by this manipulation. Many uses of the Holocaust are in many senses forms of manipulation. Even the speakers know that what they are saying is untrue. | |||

L.I.: And when every possibility for direct contact to the survivors and their memories is gone, and I put aside filmmed testinomies and artifacts from the era, when I am asking this question - all of the memory will be in the hands of agents of memory that are not necessarily obliged to the facts. The question is, what content will be poured into the memory then? | |||

R.S.: Well, as I see it, the Holocaust is already today, and in fact it is not even such a recent phenomenon, subjected to the actions of agents of memory. And it has been this way for a long time already. | |||

I do not find it a big matter, in this respect, that the last Holocaust survivors would soon all pass away. So yes, you could say that today Holocaust survivors still speak out and tell their personal stories and memories, but it is not what it used to be. It does not play the same role anymore. | |||

It is clear that we have been under the influence of agents of memory for a long time already. And it is clear to say... well, this is not a pleasant thing to say, but the Holocaust today does not ‘need’ the survivors any longer. This is a very hard claim to make, I am aware of that, but the Holocaust has already become such a central core in our essance, in the entire human conscience. It does not matter whether or not non-Jews perceive the Holocaust exactly the same way us Jews do. What is important is that the Holocaust has become a central ingredient in the human consciousness, it is accepted as a universal founding historical event. | |||

Take the word ‘Auschwitz’, for example. It is nowadays an international word with a lot of context. Not only in our own national aspects, but in the aspects of a place of industrialized murder, genocide. It is a symbol for immense human suffering and horrible atrocities. For all it is worth, I do not see how the passing away of the last Holocaust survivor, and in fierce contrast to that, the death of the last perpetrator, would have any affect on this subject. It is already so well rooted in the human existence. | |||

L.I.: So according to what you say, would it not eventually be possible to pour in any desirable content into the narration of the Holocaust? | |||

R.S.: Look, the answer is yes. We can pour in any content into a narrative. | |||

We have all experienced a recent example for such case with the story of Benjamine Netanyahu’s public claim for Haj Amin Al-Husseini’s role in the Final Solution. | |||

One can pour in anyting, and I repeat the saying that the Holocaust is a sacred story. Just as you can interpret or distort the Torah, which people indeed do. This is the relation to the mythic sense of the Holocaust. Our role as historians is to say what did happen and what did not happen. | |||

In the story of Al-Husseini, there was indeed a front line of historians who stood up saying that the Israeli Prime Minister expresses things that did not happen. I do not even know if it was not just a manipulation on his account. Netanyahu did not appear to be very bothered with the criticism, at least so it seemed. It seemed as if his view was something like: “Okay, so that’s not exactly how things were...”. And yes, history moves in two directions - there are the collective memory and the myth, both deal with whichever consequences they desire. On the | |||

=== Prof. Dr. Eran Neuman === | |||

=== Dr. Gadi Taub === | |||

=== Prof. Yair Garbuz === | |||

== Part IV: '''Memorial Study''' == | |||

== Part V: '''Site Analysis''' == | |||

== Part VI: '''Concepts''' == | |||

== Part VII: '''Planning''' == | |||

Latest revision as of 13:11, 1 April 2020

Holocaust Recollections - Commemorative Architectural Representation of the Holocaust in Israel

Project Description

The current phase of the project begins with the death of my grandmother in 2018, and our family's loss of the last remaining person to carry any sort of personal, rather than collective, memories from the time-period of the Holocaust.

My thesis claims that within the Israeli society, where Holocaust commemoration is ever so present, its public representation has always been linked to, and effected by, the living-personal-memory and testimony of the victims.

These days, however, we are facing the unfortunate end of an era with the loss of the very last Holocaust survivors and so, our memory of this time-period relies solely on top-down narrated collective memory and the formally-formed written and spoken ethos of this major historical event, rather than being also greatly effected by organic, bottom-up personal memory. My belief is that within the Israeli society, this heavy-weight swift in memory balance from the "possibly-personal" to the "inevitably-collective" should contextualize a new discourse in the field of Holocaust commemoration and how it is remembered and presented in the public sphere.

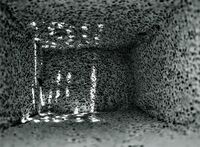

My project takes place in Independence park in Tel Aviv, Israel, at the edge of a cliff overlooking the sea. The site currently has an ad-hoc planned path connecting the cliff promenade and the beach promenade. My intention is to plan a Holocaust commemorative site in Israel which incorporates a "mundane" function - id est a connecting stairwell - into the "near-holy" commemorative monument, and challenge the concept of what-and-how remembering the Holocaust in Israel may become. The idea is to open discourse and try to allow a wider sheet of representation for different memories, personal ones, which would in turn enhance and fill-in the missing pieces that the often told collective ethos cannot provide.

Before final planning of the project, I first aim to built a wide-scale try-and-error sandpit of conceptual and spatial ideas which would in turn eventually develop into the concretisation of the monument.

Part I: Program

Part II: Anthropology Essay

Part III: Interviews & Conversations

Establishing a critical idea and defining an approach, is the first building-stone in developing my architectural work, as I strongly believe in the dialectic nature of social aspects that form architecture, which in turn, transforms society. Architecture is a language, a form of expression that makes concrete an abstract idea. It is a pure representation of a given time and place, of an epoch and mindset. Hence, my work ahead must begin with identifying unambiguously my area of intervention; Israel, 2018. How would the architectural representation of the Holocaust develop throughout the lives of 3rd generation survivors; when the last individual who bears their immediate personal memories of the Holocaust pass away? To answer this question, I will first assess and define my contextual situation.

Recallection of Loss? Once a year, every year, 86% of the Jewish population of Israel stands still in silence for 120 seconds. In their minds they imagine and replay the most horrific event that happened to the Jewish People in modern history - The Holocaust. This memorial “minute of silence”, which actually lasts for two minutes, takes place on the Israeli Memorial Day for the Holocaust and Heroism, held annually on the 27th day of the month of Nisan, marked on the Hebrew calendar. But what exactly do all these people remember?

As time goes by, the Holocaust changes its nature from a concrete historical event, such that can be talked about, discussed in an academic manner and referred to by documents and historical facts, to a timeless event of mythical proportions, deprived of any real contextual basis. As part of this process, one might suggest that in Israel, the state makes use of the Holocaust to achieve goals that may indeed be to the benefit of the country and its people, but consequently turn the historical event into a tool - The Holocaust for itself loses its position as the main focal point and no one truly bothers with its effect on the way it is widely remembered and understood colloquially. It would have been logical to assume that as years go by and the State of Israel becomes a stronger and a better established country, the magnitude of anxiety, the so called “fear factor” of the Jewish Israeli People, should diminish. Yet, on a poll conducted by an Israeli newspaper in 2013 (2), 49% of all Jewish Israelis said that they believe a second Holocaust for the Jewish People is highly likely to happen in the future. On a similar poll held in the 1970s among Holocaust Survivors, which asked if they believed a second Holocaust is likely to happen to the Jewish People, only 46% of the inquired answered “Aye”.

In Israel of today, it appears that the narrative of the Holocaust is unfortunately, oftentimes detached from its contextual history.

It is widely accepted that in the past, during the first decades for the young country of Jewish immigrants, this horrific event was used by the leadership to establish a solid collective identity for Jews of different geographic and ethnic backgrounds, whereas today, it is institutionally turned into the “ultimate event of horror” which Israeli Jews experience as individuals, rather than as a group. One could therefore even wonder: What is the public role of the Holocaust in Israel, when the state finds it difficult to even offer the proper care and institutional old-day respect for Holocaust survivors, in the last years on their lives?

The KZ Syndrome, or, Survivor Guilt The Konzentraztionslager Syndrome is a prevalent and prevailing mental condition which occurs when an individual believes he or she have done something wrong by their very survival of the horrors of the Holocaust. It is accepted today as a significant extreme symptom of a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

A Post-traumatic event is “stored” in the human brain differently than a normal memory of a past experience; such memories of profound fear and angst never make the typical process from a short-term memory to the deeper, more vague long-term memory. They remain fresh and vigilant, as if the event of horror only recently happened. The panic, the anxiety, the sights, the smells, the feelings - all the emotions that were experienced during the painful event are re-lived. For the victim, they come back to life in the here and now. For the Holocaust survivor, the war has never ended; it is still going on, it is still a daily struggle.

The Holocaust, 1939 - ... A non-immediate portion of the war and its horrors is still with us today through the fears and lives of second and third generation survivors.

In a 2015 study conducted by Dr. Rachel Yehuda (3), she revealed that Post Traumatic events cross generations and transfer on to one’s offsprings through a change in the genetic sequance and subconscious psycological recations.

Decades before the existence of the State of Israel, the natural thought of the early leaders of the Zionist Movement was to rely on Central and Eastern European Jewry for the future population of the country.

After the tragic and terrible human losses of the Holocaust, as the State of Israel was established, hundred of thousands of Jews emigrated to it from the Arab world. The social composition of the country started changing - Israel turned into a Jewish multicultural society.

The local leadership had to find a consolidating narrative to help turn all the different people, with all different backgrounds and different languages, into a monolith nation with a single identity. The Holocaust was turned into a pathos melting pot of a unifying victim ethos.

One of the strongest examples to this type of usage of the Holocaust as a tool was frequently done by no other than the late Prime Minister of Israel, Menachem Begin, whose parents perished at the hands of the Nazis. However, the truth remains as all streams of the political spectrum in Israel, whether belonging to the Right or to the Left, either done by Ashkenazim or by Sepharadim, everyone made and makes use of the Holocaust as a tool.

Forgive and Forget? On a 2015 survey conducted for the 50th anniversary of the official diplomatic relations between Israel and Germany (4), 69% of the represented Israelis held a positive perspective towards modern-day Germany, which may bring up the question: How is it possible that in Israel, out of all places, the Holocaust has been detached from its historical roots in Germany?

Yet, as matter of fact, to formulate memories of a distant historical event, it does not matter where on earth the event originally took place. For all its worth, there seem to be no external circumstances, only subjects with personal memories; or as the controversial quote said by the former Prime Minister of Great Britain, Margaret Thatcher: “There is no such thing as society; there are only individual men and women, and there are families”.

The memory of the Holocaust in Israel today is arranged exactly by this condition, which sadly allows manipulation for almost any contemporary need. In order to manipulate a traumatic historical event, it must first be turned into a set of fears. The question which arises: Has anyone turned the Holocaust into a set of fears deliberately?

In my opinion, not necessarily. This result was the outcome of a larger, slow process of transformation from an adhesive common identity to a deconstructing individual identity. In other words, a form of “social privatization” which led eventually to turning a historical event into a practical, political tool.

In Naomi Klein’s book “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism”, the researcher describes the way the masses can be controlled through a constant stage of fear, horror and a sense of helplessness. Who could possibly deal with mundane topics when one’s very existence is on the line?!

In a similar manner, the Holocaust within the Israeli discourse became just that. It was detached from its historical context and was turned into the ultimate, infinite evil. A tool through which an entire nation stays in a constant Post-traumatic Disorder for over 70 years.

The biggest question I want to ask with my work is whether it is possible to recollect and represent the Holocaust in the Israeli public sphere, in other alternative ways as well; ways that impose less indoctrination and offer fewer summoned answers. The alternative commemoration I seek should allow an open-end for thoughts and feelings.

In 1988 the late Israeli historian Dr. Yehuda Elkana, a Holocaust survivor himself, published a controversial article in the Israeli newspaper Ha’Aretz, by the title “The Need to Forget” (5), in which he emphasizes his personal point of view that there is no greater risk for the future of the State of Israel than the ever-present traumatic memory of the Holocaust in the national consciousness.

Dr. Elkana argues that the anxiety of the Holocaust is breastfed to every boy and girl in Israel from the age of infancy, that the educational system in Israel sends the youth year after year to repeated visits in Yad VaShem, visits which create memories that the youth cannot benefit or escape from. He argues that the nation must let go of the bleak past, try to put the trauma behind and strive to heal, for its own benefit and for its own future survival.

We Won’t Forget; We Won’t Forgive! In August 2016, my wife and I went on a three-week long summer vacation to Poland. It was my first ever visit to the country. We rented a car and drove across it from East to West. We had all the time we needed to explore anywhere we wanted.

During this trip, my wife kept asking, just as she had done before we even arrived to Poland, why should we not see any of the Death Camps, or at least Auschwitz-Birkenau, as we were staying in Krakow for several days and the site is nearby. It was certainly interesting to see, she argued.

My answer to her was that I don’t need to visit Auschwitz-Birkenau as I have already been there. In fact, I visit the place several times every week and perhaps, I never left.

A visit to a Death Camp is an experience I personally do not feel the need for. The educational purpose of it is unnecessary for my knowledge, as I know pretty much already know everything there is to know about the Holocaust and the Death Camps. For me, it is not vital to see piles of victim’s shoes or forsaken crematoriums with my own two eyes. I know what happened, I feel very deeply about it and its physical existence cannot contain any new message for me to grasp on, except for grief and hurt; grief and hurt that are already a part of who I am.

Moreover, the unimaginable evilness that gave rise to the Holocaust is not to be found in the barbed-wires and train tracks of Auschwitz. It is also not to be found in any gas-chamber or a crematorium. This monstrous viciousness lied only within the wicked hearts of those who stood behind it. Once I understood that, I figured out I do not need to visit any death-camp.

Yet, during this trip we did visit a small town by the name of Sokołów Podlaski, about an hour-and-a-half drive Northeast of Warsaw, where my late grandfather used to live. I tried to find the now non-existing synagogue, the old Jewish school my grandfather used to attend, and see what life must have been like for him, living there.

It is very likely that for many non-Jews, perhaps for some Jews too, a visit to a Death Camp is an important educational study-trip, much more than a visit to a random, forgotten Polish town. The sites of the camps are of an utmost historical importance - there is no doubt about that. Although personally, it is an unnecessary trip. For me, seeking a “living past” is more intriguing and relevant than finding the place where this past was put to an abrupt and unjust end.

In our visit to Poland, I tried to experience the country as little as possible through the lens of the Holocaust. It may be quite impossible for a third-generation Jewish survivor, it may be impossible for an Israeli who grew up in the country and was raised there - but nonetheless, I tried.

During our three-week stay in Poland we did not visit a single Death Camp.

Dr. Dr. Roni Stauber

Lior Israel: How would you define the memory of the Holocaust and its presence within the Israeli civic sphere since the founding of the country?

Roni Stauber: The process that happened to the Holocaust in Israel over the years is that it has become a ‘civil religion’. I suppose you have already encountered this claim, as I am not the first to have said that. I say ‘civil religion’ since it certainly has the right characteristics and hallmarks of sanctity.

How is it manifested? Well, indeed when the term ‘Holocaust’ is at use, sometimes, or even frequently in many different analogies, it may often create a negative reaction among the public which asks: “Why would anyone use the Holocaust’s name for such purposes?!”.

Some do view its mundane use as a desecration of something holy, or a form of blasphemy. There is always a debate around it. It is not a neutral concept as many other concepts are. The Holocaust, in this sense, is a bit like the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem - something holy.

But the Holocaust has not always been this way. It has gone through changes in the Israeli society. The Holocaust was not seen the way it is seen nowadays in the 1950s, for example. As we become further distant from the actual happenings and events, the Holocaust is not perceived as just ‘another’ historical event, as one would have imagined, but quite the contrary - it grows into mythic sizes. It is a paradoxical manner that is true in correlation to the Holocaust not only in Israel.

The normal process that happens with other historical events does not seem to happen in the case of the Holocaust.

The fact is that a lot of effort in research and study is carried out about the Holocaust. I would ask to separate the public discourse in the topic from the research activity attitudes, since it is the research activity that truly puts one ‘into’ the Holocaust; Which brings it down from its mythic pedestal back to earth, and allows us to have greater insights.

Yet, as Friedländer and others researchers have said, one is still unable to fully comprehend the meaning of what Auschwitz actually was. The gap is ever-present, we know that, but from many standpoints the research does shed light on the more ‘practical’ sides of the Holocaust - it helps to understand what brought the perpetrators to such moral abyss, it assists to the understanding and mapping of Nazi bureaucracy, attempts to explain the personal aspects that eventually sum up into this monstrous creation. And indeed, this monstrous creation has many personal sides to it - career aspirations, obedience, bureaucracy and scary personal sides - some things we may even recognize in our day to day lives - of course that not even close to these horrifying scales, but it is still there.

So again, the research regards the Holocaust as a historic event and analyzes it as such. Even if it is viewed as a precedential and an infrequent, rare event of a state’s defined decision to carry out a complete and total genocide of anther People.

The question that is asked is how much of this concept gets through into the Israeli society and its discourse about the Holocaust - but this is a question I unfortunately cannot answer.

That is to say that in Israel the Holocaust is acted as a myth, a sacred story - for better or for worse. We can discuss it. It is a key element in the Israeli civilian identity and identity of the State.

This is the point where I always say that if you look at the terms ‘Holocaust’ and ‘Revival’: These two terms are key definitions - a combination of words that is basic for the understanding of the Holocaust in Israel. I find it very interesting to see the changes, and this is my own claim, that this combination of words has gone through.

As for my own perception, and you can back it up with my writings if you will, is that in the 1950s the emphasis in Israel was completely on the part of revival and resurrection and the Holocaust was only perceived as a sort of the “bringing forward” for it - as if the Holocaust were the historic explanation for the later events of Jewish revival and resurrection.

I claim, and I know that not everybody agrees with me, that the dealing with the Holocaust during that time was seen only through the so-called ‘lessons’ we could have take from it, or what conclusion we could have taken from it. But at the same time there was nearly no dealing with the stories of the Holocaust, the atrocities, and catastrophes.

This tendency changed over the years, however. As it changed, and since the survivor’s stories from the Holocaust are so horrific and hard to comprehend, just think of Auschwitz-Birkenau as an example, the Holocaust ended up being molded into ever growing mythic proportions.

L.I.: In what manner do you think the Holocaust should have been remembered in Israel and what should be the way to approach it in the Israeli society?

R.S.: First I must say that I am not fond of the mythic outlook of the Holocaust. In my opinion, it must be taken as a historic event, while keeping in mind all of its true uniqueness and scope, which obligates us to analyze and understand it in non-biased tools.

It should be taken as a lesson for the entire human race, which may also have some national sides, but again, it should mostly be a very important universal message. We should understand the consequences of human behaviour and try to examine the dynamics of mass killings and genocides, how such atrocities begin and carry on happening after people see what they have done, and inspecting the mechanism of bureaucracy - how dangerous and scary it may become when it is pushed into negative extremes. This is what we should understand from it - the alarm from radical, extreme ideologies, from the downfall of society to abyss and collective insanity.

The problem is that because the Holocaust is seen as a sacred thing, because it was turned into a myth and as such, it serves educational purposes - people may extract very contradicting conclusions from it. I would even say that this is one of the defining attributes of the approach towards the Holocaust in the Israeli society today - i.e. people use the story for their own needs. It is the same process that may be done with the Torah. Some may extract territorial and national justifications from it, sometimes even nationalistic justifications - while others may find universal truths such as saying that the Torah calls for equality and peace among nations and mankind, and some others may say that it mostly expresses the right of the Jewish people for this land. It is all possible.

The same principle applies for the Holocaust - if you take the conclusions of the right-wing from it, then their claim sounds something like: “Look at what they have done to us!”, or “Everyone is against us, therefore we must only rely on ourselves!”, and so on - while the left-wing side would try to take it to a universal idea and the fear of what can happen to a society, or maybe to the Israeli society in our case, when people fall into a moral black hole.

I, as a historian... look, broadly speaking, historians analyze every event as a distinct happening - the concept is that every event is unique. This is the basic perception of any historical research. It interests us to examine an incident, a happening.

A historian, as opposed to a Political Science researcher, does not try to find any formulas or repetitional rules. I could even say that we are afraid of general rulings and all-inclusive conclusions, patterns. I am taken aback by analogies. I am very un-fond of it and I do not deal with such things.

Of course that each and every one of us has his/her own thoughts and opinions, but I am very troubled as a historian when personal opinions become the basis for historical analogies. I would have been a lot happier if people dropped aside the analogies of the Holocaust - from both sides, left and right. We should only focus on it as a unique historical event - not a myth that should lead us to an understanding, whatever it may be. We should only understand the Holocaust as a specific, one-time event.

L.I.: Would you say the Israeli society suffers from a post-trumatic disorder due to the memories of the Holocaust?

R.S.: If the claim states that our entire behaviour as a society is irretional due to the Holocaust - No, I would not accept it. Though, of course the question must also refer to the relevant time this post-traumatic disorder relates to.

I think that within the Israeli society there were two opposing forces, existing side by side already from the very beginning of the state. One force pushed towards Holocaust oriented conscienceness, while the other force pushed into other directions, so that the Holocaust would not become a decisive factor in the state’s relation to the rest of the world. You could notice these two forces already from the very estabhlishment of the State, and these forces naturally collide.

My own opinion is that the decisive matters that determine which part of the Holocaust memory is more dominant, for example - the fear from our destruction by our enemies or the chance for peace - these are the factors of our surrounding circumstances. It is not that we correspond with every event in a post-traumatic behaviour that is detached from reality. I believe that the plain reality does affect our opinions and actions directly. When our true reality is full of concerns about the future, there is existential fear - I do not rule out that the experiences we have had as a People, our collective memory, do henhance this sense of fear. Even if our shared memory exaggerates our emotions - our emotions are still not un-related to reality.

It is not as if our lives here in Israel are the same as the lives of the people in peaceful Scandinavia, and we just make up imaginary threats and fears that do not really exist around us. We do indeed live in an intimidating part of the world.

But it would be improbable to claim that the Holocaust has absolutely no connection to our perception. How could it not? It is part of our memory and conscieneness. Yet, going all the way in claiming that the Israeli society acts the way it does in disconnection with reality and only according to the traumas of the Holocaust; that the Israeli society is completely neurotic and so its acts out of fear and blindness, rather than directly reacts to the situation around it, that is to say, that our alleged actions are only reactions to our memories - no, this is a stand I cannot accept.

I think that our reactions are results of the real world. They could perhaps be over-manifested, and it may as well be that the Israeli fear from Iran, for example, is over-reacted - but such claims I cannot be sure of. I do not possess all the intelegence and information of how dangerous or hateful the Iranians are - but anyway, the Israeli fear is certainly not detached from reality.

To summarize my words - it is obvious that there is influence to the Holocaust, but on the other hand, our actions are not post-traumatic in the sense that we allegedly act in disassosiation with reality. I believe we act rather rationally, sometimes even very rationally, in fierce contrast to what one would expect - Take for example the case with Israel during the Gulf War. One would expect Israel to act in a non-rational manner and retaliate, strike back in Iraq for their missile attacks on Israel. However, the Israeli leadership did no do that. There are other examples where the State of Israel does not act according to what one could expect from a post-traumatic society. This means that there is rational thinking which is rooted in hard facts and reality.

It may or may not be stratigically correct - this is a matter for other debates - but I do not see the Israeli behaviour as such that is not connected to reality and that we should have all been put into a mental institute, as a nation.

L.I.: Does it mean that in your eyes, the presence of the Holocaust in the Israeli day to day life is more or less normal, taking into accounts the very abnormal event?

R.S.: Yes, in my opinion is it a normal reaction. Memory contradicts with reality in re’al politics. I do not see it as a dichotemy that one side is up and the other is down, as a zero-sum game - that is, that the reason’s side is kept down. I believe that there is contradiction in this as there is in many human behaviours. This means that one might have fears and memories of traumas one has gone though, this may be relevant to each and every one of us, and then we come across the reality and the question that arises is which part overpowers the other.

In my opinion there is a collision between the two things; the Holocaust is present and affecting. I do not think it took over our minds, our ways of thinking and the behaviour of the Israeli society. I do not see it this way.

Although there are undoubtly leaders who exaggerate - I am not completely sure how much of what they say is real and how much of it is just a form of manipulation - but when Netanyahu says this and that, I am not sure whether he truly believes in what he says or simply manipulates the situation. I am sure he fully understands the historical differences between different events. There is a lot of disinformation among politicians in general, and this is another reason why I do not like what they make of it. I am taken aback by this manipulation. Many uses of the Holocaust are in many senses forms of manipulation. Even the speakers know that what they are saying is untrue.

L.I.: And when every possibility for direct contact to the survivors and their memories is gone, and I put aside filmmed testinomies and artifacts from the era, when I am asking this question - all of the memory will be in the hands of agents of memory that are not necessarily obliged to the facts. The question is, what content will be poured into the memory then?

R.S.: Well, as I see it, the Holocaust is already today, and in fact it is not even such a recent phenomenon, subjected to the actions of agents of memory. And it has been this way for a long time already.

I do not find it a big matter, in this respect, that the last Holocaust survivors would soon all pass away. So yes, you could say that today Holocaust survivors still speak out and tell their personal stories and memories, but it is not what it used to be. It does not play the same role anymore.

It is clear that we have been under the influence of agents of memory for a long time already. And it is clear to say... well, this is not a pleasant thing to say, but the Holocaust today does not ‘need’ the survivors any longer. This is a very hard claim to make, I am aware of that, but the Holocaust has already become such a central core in our essance, in the entire human conscience. It does not matter whether or not non-Jews perceive the Holocaust exactly the same way us Jews do. What is important is that the Holocaust has become a central ingredient in the human consciousness, it is accepted as a universal founding historical event.

Take the word ‘Auschwitz’, for example. It is nowadays an international word with a lot of context. Not only in our own national aspects, but in the aspects of a place of industrialized murder, genocide. It is a symbol for immense human suffering and horrible atrocities. For all it is worth, I do not see how the passing away of the last Holocaust survivor, and in fierce contrast to that, the death of the last perpetrator, would have any affect on this subject. It is already so well rooted in the human existence.

L.I.: So according to what you say, would it not eventually be possible to pour in any desirable content into the narration of the Holocaust?

R.S.: Look, the answer is yes. We can pour in any content into a narrative. We have all experienced a recent example for such case with the story of Benjamine Netanyahu’s public claim for Haj Amin Al-Husseini’s role in the Final Solution.

One can pour in anyting, and I repeat the saying that the Holocaust is a sacred story. Just as you can interpret or distort the Torah, which people indeed do. This is the relation to the mythic sense of the Holocaust. Our role as historians is to say what did happen and what did not happen.

In the story of Al-Husseini, there was indeed a front line of historians who stood up saying that the Israeli Prime Minister expresses things that did not happen. I do not even know if it was not just a manipulation on his account. Netanyahu did not appear to be very bothered with the criticism, at least so it seemed. It seemed as if his view was something like: “Okay, so that’s not exactly how things were...”. And yes, history moves in two directions - there are the collective memory and the myth, both deal with whichever consequences they desire. On the