Holocaust Recollections, Lior Israel

Holocaust Recollections - Commemorative Architectural Representation of the Holocaust in Israel

Project Description

The current phase of the project begins with the death of my grandmother in 2018, and our family's loss of the last remaining person to carry any sort of personal, rather than collective, memories from the time-period of the Holocaust.

My thesis claims that within the Israeli society, where Holocaust commemoration is ever so present, its public representation has always been linked to, and effected by, the living-personal-memory and testimony of the victims.

These days, however, we are facing the unfortunate end of an era with the loss of the very last Holocaust survivors and so, our memory of this time-period relies solely on top-down narrated collective memory and the formally-formed written and spoken ethos of this major historical event, rather than being also greatly effected by organic, bottom-up personal memory. My belief is that within the Israeli society, this heavy-weight swift in memory balance from the "possibly-personal" to the "inevitably-collective" should contextualize a new discourse in the field of Holocaust commemoration and how it is remembered and presented in the public sphere.

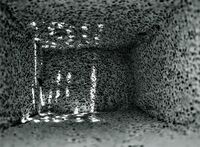

My project takes place in Independence park in Tel Aviv, Israel, at the edge of a cliff overlooking the sea. The site currently has an ad-hoc planned path connecting the cliff promenade and the beach promenade. My intention is to plan a Holocaust commemorative site in Israel which incorporates a "mundane" function - id est a connecting stairwell - into the "near-holy" commemorative monument, and challenge the concept of what-and-how remembering the Holocaust in Israel may become. The idea is to open discourse and try to allow a wider sheet of representation for different memories, personal ones, which would in turn enhance and fill-in the missing pieces that the often told collective ethos cannot provide.

Before final planning of the project, I first aim to built a wide-scale try-and-error sandpit of conceptual and spatial ideas which would in turn eventually develop into the concretisation of the monument.

Part I: Program

Part II: Anthropology Essay

Part III: Interviews & Conversations

Establishing a critical idea and defining an approach, is the first building-stone in developing my architectural work, as I strongly believe in the dialectic nature of social aspects that form architecture, which in turn, transforms society. Architecture is a language, a form of expression that makes concrete an abstract idea. It is a pure representation of a given time and place, of an epoch and mindset. Hence, my work ahead must begin with identifying unambiguously my area of intervention; Israel, 2018. How would the architectural representation of the Holocaust develop throughout the lives of 3rd generation survivors; when the last individual who bears their immediate personal memories of the Holocaust pass away? To answer this question, I will first assess and define my contextual situation.

Recallection of Loss? Once a year, every year, 86% of the Jewish population of Israel stands still in silence for 120 seconds. In their minds they imagine and replay the most horrific event that happened to the Jewish People in modern history - The Holocaust. This memorial “minute of silence”, which actually lasts for two minutes, takes place on the Israeli Memorial Day for the Holocaust and Heroism, held annually on the 27th day of the month of Nisan, marked on the Hebrew calendar. But what exactly do all these people remember?

As time goes by, the Holocaust changes its nature from a concrete historical event, such that can be talked about, discussed in an academic manner and referred to by documents and historical facts, to a timeless event of mythical proportions, deprived of any real contextual basis. As part of this process, one might suggest that in Israel, the state makes use of the Holocaust to achieve goals that may indeed be to the benefit of the country and its people, but consequently turn the historical event into a tool - The Holocaust for itself loses its position as the main focal point and no one truly bothers with its effect on the way it is widely remembered and understood colloquially. It would have been logical to assume that as years go by and the State of Israel becomes a stronger and a better established country, the magnitude of anxiety, the so called “fear factor” of the Jewish Israeli People, should diminish. Yet, on a poll conducted by an Israeli newspaper in 2013 (2), 49% of all Jewish Israelis said that they believe a second Holocaust for the Jewish People is highly likely to happen in the future. On a similar poll held in the 1970s among Holocaust Survivors, which asked if they believed a second Holocaust is likely to happen to the Jewish People, only 46% of the inquired answered “Aye”.

In Israel of today, it appears that the narrative of the Holocaust is unfortunately, oftentimes detached from its contextual history.

It is widely accepted that in the past, during the first decades for the young country of Jewish immigrants, this horrific event was used by the leadership to establish a solid collective identity for Jews of different geographic and ethnic backgrounds, whereas today, it is institutionally turned into the “ultimate event of horror” which Israeli Jews experience as individuals, rather than as a group. One could therefore even wonder: What is the public role of the Holocaust in Israel, when the state finds it difficult to even offer the proper care and institutional old-day respect for Holocaust survivors, in the last years on their lives?

The KZ Syndrome, or, Survivor Guilt The Konzentraztionslager Syndrome is a prevalent and prevailing mental condition which occurs when an individual believes he or she have done something wrong by their very survival of the horrors of the Holocaust. It is accepted today as a significant extreme symptom of a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

A Post-traumatic event is “stored” in the human brain differently than a normal memory of a past experience; such memories of profound fear and angst never make the typical process from a short-term memory to the deeper, more vague long-term memory. They remain fresh and vigilant, as if the event of horror only recently happened. The panic, the anxiety, the sights, the smells, the feelings - all the emotions that were experienced during the painful event are re-lived. For the victim, they come back to life in the here and now. For the Holocaust survivor, the war has never ended; it is still going on, it is still a daily struggle.

The Holocaust, 1939 - ... A non-immediate portion of the war and its horrors is still with us today through the fears and lives of second and third generation survivors.

In a 2015 study conducted by Dr. Rachel Yehuda (3), she revealed that Post Traumatic events cross generations and transfer on to one’s offsprings through a change in the genetic sequance and subconscious psycological recations.

Decades before the existence of the State of Israel, the natural thought of the early leaders of the Zionist Movement was to rely on Central and Eastern European Jewry for the future population of the country.

After the tragic and terrible human losses of the Holocaust, as the State of Israel was established, hundred of thousands of Jews emigrated to it from the Arab world. The social composition of the country started changing - Israel turned into a Jewish multicultural society.

The local leadership had to find a consolidating narrative to help turn all the different people, with all different backgrounds and different languages, into a monolith nation with a single identity. The Holocaust was turned into a pathos melting pot of a unifying victim ethos.

One of the strongest examples to this type of usage of the Holocaust as a tool was frequently done by no other than the late Prime Minister of Israel, Menachem Begin, whose parents perished at the hands of the Nazis. However, the truth remains as all streams of the political spectrum in Israel, whether belonging to the Right or to the Left, either done by Ashkenazim or by Sepharadim, everyone made and makes use of the Holocaust as a tool.

Forgive and Forget? On a 2015 survey conducted for the 50th anniversary of the official diplomatic relations between Israel and Germany (4), 69% of the represented Israelis held a positive perspective towards modern-day Germany, which may bring up the question: How is it possible that in Israel, out of all places, the Holocaust has been detached from its historical roots in Germany?

Yet, as matter of fact, to formulate memories of a distant historical event, it does not matter where on earth the event originally took place. For all its worth, there seem to be no external circumstances, only subjects with personal memories; or as the controversial quote said by the former Prime Minister of Great Britain, Margaret Thatcher: “There is no such thing as society; there are only individual men and women, and there are families”.

The memory of the Holocaust in Israel today is arranged exactly by this condition, which sadly allows manipulation for almost any contemporary need. In order to manipulate a traumatic historical event, it must first be turned into a set of fears. The question which arises: Has anyone turned the Holocaust into a set of fears deliberately?

In my opinion, not necessarily. This result was the outcome of a larger, slow process of transformation from an adhesive common identity to a deconstructing individual identity. In other words, a form of “social privatization” which led eventually to turning a historical event into a practical, political tool.

In Naomi Klein’s book “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism”, the researcher describes the way the masses can be controlled through a constant stage of fear, horror and a sense of helplessness. Who could possibly deal with mundane topics when one’s very existence is on the line?!

In a similar manner, the Holocaust within the Israeli discourse became just that. It was detached from its historical context and was turned into the ultimate, infinite evil. A tool through which an entire nation stays in a constant Post-traumatic Disorder for over 70 years.

The biggest question I want to ask with my work is whether it is possible to recollect and represent the Holocaust in the Israeli public sphere, in other alternative ways as well; ways that impose less indoctrination and offer fewer summoned answers. The alternative commemoration I seek should allow an open-end for thoughts and feelings.

In 1988 the late Israeli historian Dr. Yehuda Elkana, a Holocaust survivor himself, published a controversial article in the Israeli newspaper Ha’Aretz, by the title “The Need to Forget” (5), in which he emphasizes his personal point of view that there is no greater risk for the future of the State of Israel than the ever-present traumatic memory of the Holocaust in the national consciousness.

Dr. Elkana argues that the anxiety of the Holocaust is breastfed to every boy and girl in Israel from the age of infancy, that the educational system in Israel sends the youth year after year to repeated visits in Yad VaShem, visits which create memories that the youth cannot benefit or escape from. He argues that the nation must let go of the bleak past, try to put the trauma behind and strive to heal, for its own benefit and for its own future survival.

We Won’t Forget; We Won’t Forgive! In August 2016, my wife and I went on a three-week long summer vacation to Poland. It was my first ever visit to the country. We rented a car and drove across it from East to West. We had all the time we needed to explore anywhere we wanted.

During this trip, my wife kept asking, just as she had done before we even arrived to Poland, why should we not see any of the Death Camps, or at least Auschwitz-Birkenau, as we were staying in Krakow for several days and the site is nearby. It was certainly interesting to see, she argued.

My answer to her was that I don’t need to visit Auschwitz-Birkenau as I have already been there. In fact, I visit the place several times every week and perhaps, I never left.

A visit to a Death Camp is an experience I personally do not feel the need for. The educational purpose of it is unnecessary for my knowledge, as I know pretty much already know everything there is to know about the Holocaust and the Death Camps. For me, it is not vital to see piles of victim’s shoes or forsaken crematoriums with my own two eyes. I know what happened, I feel very deeply about it and its physical existence cannot contain any new message for me to grasp on, except for grief and hurt; grief and hurt that are already a part of who I am.

Moreover, the unimaginable evilness that gave rise to the Holocaust is not to be found in the barbed-wires and train tracks of Auschwitz. It is also not to be found in any gas-chamber or a crematorium. This monstrous viciousness lied only within the wicked hearts of those who stood behind it. Once I understood that, I figured out I do not need to visit any death-camp.

Yet, during this trip we did visit a small town by the name of Sokołów Podlaski, about an hour-and-a-half drive Northeast of Warsaw, where my late grandfather used to live. I tried to find the now non-existing synagogue, the old Jewish school my grandfather used to attend, and see what life must have been like for him, living there.

It is very likely that for many non-Jews, perhaps for some Jews too, a visit to a Death Camp is an important educational study-trip, much more than a visit to a random, forgotten Polish town. The sites of the camps are of an utmost historical importance - there is no doubt about that. Although personally, it is an unnecessary trip. For me, seeking a “living past” is more intriguing and relevant than finding the place where this past was put to an abrupt and unjust end.

In our visit to Poland, I tried to experience the country as little as possible through the lens of the Holocaust. It may be quite impossible for a third-generation Jewish survivor, it may be impossible for an Israeli who grew up in the country and was raised there - but nonetheless, I tried.

During our three-week stay in Poland we did not visit a single Death Camp.